Qiu Changhong: Guardian of Nature for 36 Years at the Sanduihe Conservation Center in Shennongjia, Hubei

Updated:2024-11-19 Source:China Green Times

During the patrol, a colleague took a photo of Qiu Changhong's smile

During the patrol, a colleague took a photo of Qiu Changhong's smile Qiu Changhong and his teammates were having lunch in the mountains during their patrol

Qiu Changhong and his teammates were having lunch in the mountains during their patrolThroughout his journey, patrol routes have changed, equipment has been upgraded, and waves of close companions have come and gone. Yet, the responsibility he bears on his shoulders has remained steadfast. Reflecting on his early days, Qiu Changhong recalls being assigned to the Laojunshan Management Office (now Laojunshan Agency of the Administration of Shennongjia National Park) for his first post. Back then, patrolling meant relying solely on his feet and a walking stick, while monitoring was done entirely with a pen and his keen eyes.

Turning back the clock to the late autumn of 1990, Qiu and his colleagues were conducting a long-distance patrol in the Laojunzhai area. Young and full of energy, he always took the lead, carrying dried rations and a tent on his back. But the weather soon turned against them. After five days of brilliant sunshine, a persistent drizzle began to fall on the sixth afternoon. They had planned to race back to the station along their original route, but an impenetrable fog obscured visibility. Lost and disoriented, unable to find their bearings, they wandered for hours as the rain intensified. The university interns accompanying them, eager to experience wilderness patrolling, stumbled repeatedly on the treacherous terrain. With no other option, they used the dim glow of their flashlights to pitch their tents, abandoning all hope of finding an exit.

The rain drummed ceaselessly on the tent. With no food left, they resorted to cupping rainwater in their hands to stave off hunger. Huddled together in their soaked clothes through the long, cold night, they fought off exhaustion, encouraging one another to hold on until dawn. Though the rain persisted the next morning, fortune smiled as the fog finally lifted. Supporting one another, they made their way down the mountain, finally reaching the station by nightfall on the seventh day.

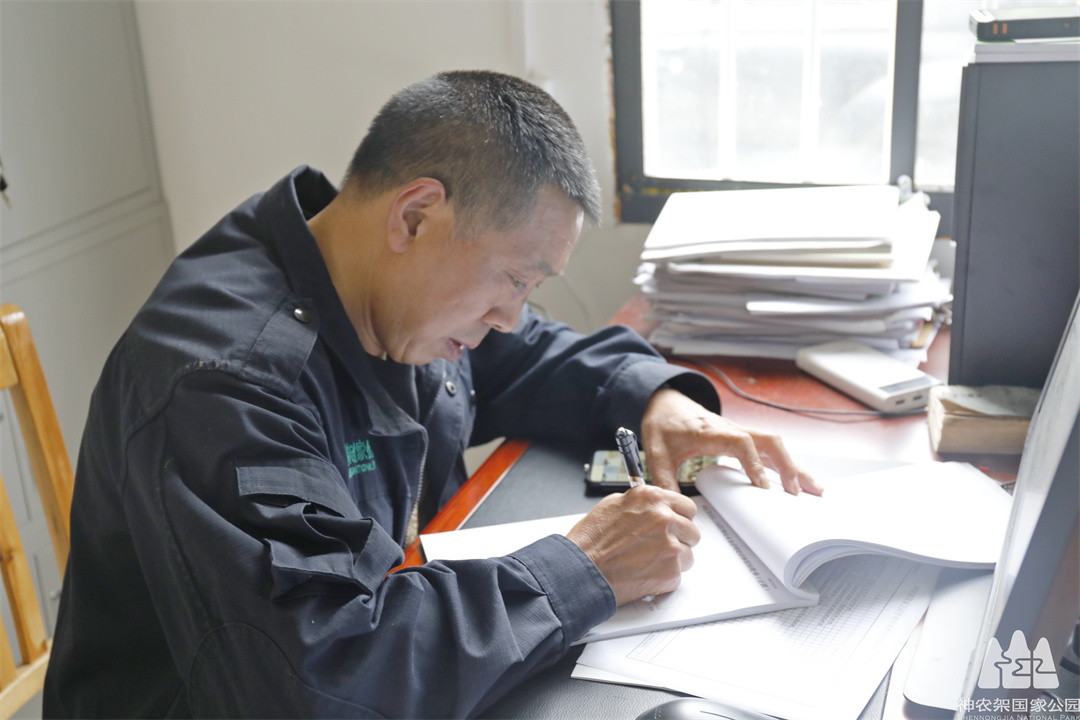

Qiu Changhong carefully fills out the work log

Qiu Changhong carefully fills out the work logOf all the natural elements encountered during his wilderness patrols, Qiu Changhong holds a special fondness for “water”. He recalls crossing paths with countless creatures—some with sharp snouts or fearsome tusks, herds of wild boar trailing behind them, and fleeting shadows of black bears slipping through the forest. Yet, none of these encounters ever frightened him. What truly worried him was the risk of not finding a water source in the vast mountain wilderness. This concern led Qiu and his colleagues to conduct targeted monitoring of water sources, trails, and other critical features during their patrols.

“In the Yunpan region, Huanghun Ridge and Dahua Rock lack water sources, while Licha River, Hou River, and Xiaodangyang have water year-round. The Caijiafang area is dominated by sheer cliffs with no passable trails, whereas Laojunzhai, Xiaodangyang, and Amituofo Pass are threaded with smaller paths. Our patrol network covers seven main routes, eighteen subsidiary routes, four monitoring plots, and twenty-one infrared cameras”, Qiu recites, his knowledge of these details as sharp and precise as if etched in stone.

He emphasized that effective conservation requires an intimate understanding of the territory—charting sheer cliffs, established roads, and winding mountain trails; identifying perennial water sources, ancient tree groves, and habitats of rare protected species; and pinpointing the areas where wildlife frequently roams. Only with such thorough, day-to-day familiarity can conservation efforts be truly targeted and effective.

The Cryptomeria fortunei planted by Qiu Changhong in October 1998 has now grown into a big tree

The Cryptomeria fortunei planted by Qiu Changhong in October 1998 has now grown into a big treeAccording to Qiu Changhong, they have established four monitoring plots and transects within their jurisdiction. While he and his team possess an intimate knowledge of the forest canopy structure in each plot and can identify dozens of understory plant species, Qiu humbly insists that in the presence of experts, he will always see himself as a student.

In 2010, during a Type II resource survey in the Dongxi region, Qiu Changhong met renowned botanist Professor Zhang Daigui. During this time, he earnestly studied under Professor Zhang. Initially, he relied on a combined approach of using both local and scientific names to memorize plant species. Through persistent learning, he developed the ability to identify over 1,000 native plants in Shennongjia. Qiu explained that plants can be identified by observing their flowers, fruits, and leaf shapes, as well as the morphology and patterns of their roots, stems, and leaves, cross-referencing these observations with photographs of type specimens. Today, Qiu Changhong is widely regarded as a “plant expert”.

During his forest patrols, Qiu always carries a notebook. For plants he doesn’t recognize, he notes their physical characteristics and takes photographs. Back at the center, he refers to plant field guides for identification. If a species isn’t documented in the books, he consults directly with Professor Zhang. To Qiu, a forest ranger’s ability to identify native plants is crucial for the effective protection and preservation of ecological resources.

Under Qiu’s leadership, the Sanduihe Management & Conservation Center has earned numerous accolades, including “Advanced Organization in Fire Prevention”, “Safe Management Center”, “Outstanding Organization of the Year”, and “Excellence Organization”. The center has also achieved multiple awards in infrared camera monitoring competitions. On a personal level, Qiu has received widespread recognition from the government and the forestry bureau of Shennongjia. His honors include “Model Worker of Shennongjia Forestry District”, “Outstanding Individual in Fire Prevention”, “Outstanding Employee”, and “Advanced Individual”. (Wang Pin & He Sai)

Address:36 Chulin Road, Muyu Town, Shennongjia Forestry District, Hubei Province 鄂ICP备18005077号-3

Phone:0719-3453368