From the Caves of Shennongjia to the Coastal Cliffs of Southeast Asia: The "Footless Birds" Travel Across China Wearing a Leg Band

Updated:2024-08-30 Source:Hubei Daily

August 14, Shennongjia. At the entrance of a cave on a steep cliff, a scholar sits cross-legged, carefully extracting a feather from a Himalayan Swiftlet (Aerodramus brevirostris). What are the migration routes and migratory patterns of the Himalayan Swiftlets in Shennongjia? Is there any connection between them and the origins and geological structure of Shennongjia? To unravel these mysteries, the Provincial Wildlife Rescue Center (Provincial Bird Banding Station) of Hubei has conducted banding and monitoring of the Himalayan Swiftlets for three consecutive years. This year, they invited Zhang Guogang, Deputy Director of the National Bird Banding Center, to provide guidance on their assessment and research work.

Scaling Cliffs and Entering Caves: Bird Banding in Action

At dawn, Zhang Guogang and more than 10 members of the Provincial Bird Banding Station set out with a day's worth of food, heading towards their work site—the Swallow Cave in Shennong Valley. These researchers, who have developed a close relationship with birds, are engaged in a little-known task: banding the Himalayan Swiftlets of Shennongjia.

Shennong Valley sits at an altitude of 2,700 meters, covered with loose rocks and thorns, making every step uphill a struggle. The team members climbed using both hands and feet along a remote cliffside path. At a corner of the path, they spotted a black cave entrance from which swiftlets occasionally flew out. These are the Himalayan Swiftlets.

Often referred to as the "footless birds" due to their extremely short legs, which make them appear legless, Himalayan Swiftlets have a unique adaptation. Zhang Guogang explains that their short legs are not conducive to perching, so they feed on insects while flying. From March to September, they breed in Shennongjia, and from September to March of the following year, they migrate to coastal cliffs in Southeast Asia for wintering. About 1.6 billion years ago, Shennongjia was a vast ocean. Whether the Himalayan Swiftlet has retained a memory of this, perceiving the caves in Shennongjia as ocean cliffs, remains an unexplored area in research.

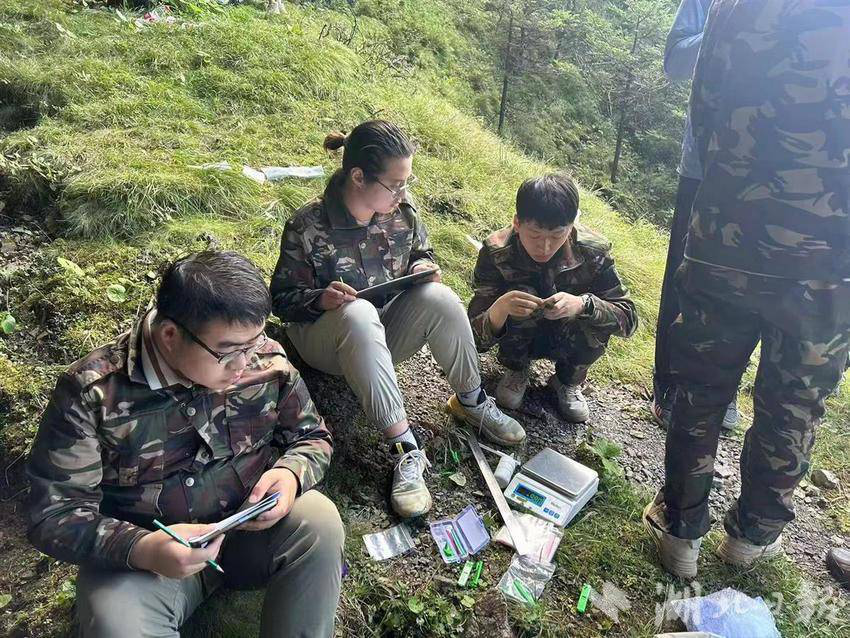

Upon reaching the designated location, the team divided into three groups: a bird capture group, a monitoring and recording group, and a sampling and photography group. The bird capture group carefully set up bird nets near the cave entrance. Feng Wei, Deputy Head of the Bird Banding Division at the Provincial Wildlife Rescue Center, explained, "These bird nets were specially developed and made by the National Bird Banding Center. The thread is very thin and soft, minimizing harm to the birds. After they fly into the net, we gently remove them."

Comprehensive Check-Up: "Diet" and Feathers Not Overlooked

Shortly after setting up the nets, three Himalayan Swiftlets were captured. The staff carefully removed the birds, placing leg bands on their right legs, and recorded their weight, body length, beak length, tarsus diameter, wing length, tail length, as well as band position, color, and number in detail.

This year, a new task was added: measuring the tarsus diameter of the Himalayan Swiftlet to ensure the custom-made leg bands are comfortable and secure.

"During flight, the Himalayan Swiftlets fly with their mouths open, catching food as they move," said Duan Mingxin, Assistant Engineer at the Provincial Wildlife Rescue Center. During banding, some swiftlets may experience stress, causing them to regurgitate their food. The team collects this regurgitated food and takes it back to the lab for analysis to better understand the diet of the Himalayan Swiftlet and to monitor the environmental quality of Shennongjia through the composition of their diet.

The sampling and photography group skillfully extracted down feathers from the abdomen of the Himalayan Swiftlet to take back to the lab for DNA analysis. This helps determine the sex of the birds and assess the phylogenetic relationship between the Himalayan Swiftlets of Shennongjia and those in Guangdong and Hainan. Zhang Guogang noted that the Himalayan Swiftlets are visually indistinguishable by sex, and blood sampling could harm them. Collecting abdominal down feathers is much safer and doesn't impact their flight.

After completing the comprehensive check-up, the staff took photos of the Himalayan Swiftlets from six angles and then released them back into the wild. The birds flew like arrows into the dense forests of Shennongjia.

Bird Banding, A Meaningful Endeavor

By noon, the banding work was still ongoing. Perched on the cliffside, the banding team took out their packed lunch—steamed buns, bread, eggs, and spicy snacks—and enjoyed a brief meal. By the end of the day, the team had banded 175 Himalayan Swiftlets. Over the past three years, the Provincial Bird Banding Station has banded over 700 Himalayan Swiftlets in Shennongjia, each carrying a unique "ID card" as they soar through the skies.

"Though bird banding is an arduous work, it is highly meaningful," Zhang Guogang explained. Bird banding is an internationally accepted technique, typically involving placing materials with special markings onto or implanting them into birds, then releasing them back into the wild. By recapturing them, observing them in the field, or using radio or satellite tracking, researchers can obtain valuable biological and ecological information about the birds. This method is an effective way to study migratory patterns and is also crucial for monitoring avian diseases and changes in habitats. China has now established a preliminary national bird banding system, forming a network of bird banding stations in key areas.

Hubei Province, known as the "Province of a Thousand Lakes", boasts rich avian biodiversity, with 580 species and over a million migratory birds wintering there annually. It is a critical part of the "East Asia-Australasia" migratory bird flyway.

In 2020, Hubei province established the Bird Banding Station, which now forms a collaborative "1+6+N" bird banding network centered on the Hubei Provincial Bird Banding Station, in cooperation with six other stations at Wanghu Lake, Longgan Lake, Chenhu Lake, Liangzi Lake, Honghu Lake, and Yichang Dalaoling region. To date, over 5,000 birds have been banded and tracked via satellite in Hubei, with initial data revealing the global migration routes of the Tundra Swan (Cygnus columbianus). Copyright Shennongjia National Park

Address:36 Chulin Road, Muyu Town, Shennongjia Forestry District, Hubei Province 鄂ICP备18005077号-3

Address:36 Chulin Road, Muyu Town, Shennongjia Forestry District, Hubei Province 鄂ICP备18005077号-3

Email:2673990569@qq.com

Phone:0719-3453368

Phone:0719-3453368

TOP